Published in The Conversation on November 15, 2016 7.21am GMT

It will be in Asia – the economic centre of the 21st century – where the future of Pax Americana (the peace that has ensued as a result of US hegemony) will be decided.

This continued existence of this peace will depend, to a significant extent, on Washington’s capacity to show that it remains a vital actor in the region despite China’s ascendancy. And, above all, that it is still the provider of security guarantees to several of China’s neighbours, such as Japan and South Korea.

If Beijing can bring its neighbours to accept its regional leadership (including its claims in the South China Sea), China could dramatically reduce US influence in a region that holds more than half of the world’s population.

That this desire would emerge in Beijing is far from surprising. No aspiring great power gains status or respect by ceding responsibility for security in its backyard to a far away foreign nation.

Chinese initiative and US pushback

To garner regional support, China has launched a series of high-profile initiatives that involve its neighbours in institutional setups: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Conference on Confidence Building Measures in Asia security architecture, and economic corridors through Pakistan and Myanmar to the Indian Ocean.

Beijing’s efforts have been derided as “chequebook diplomacy” and China has been accused of trying to buy friends. But if successful, the country’s endeavours will contribute to the creation of an increasingly Sinocentric Asia.

China’s most ambitious project is the New Silk Road Economic Belt, usually referred to as One Belt One Road. This proposed economic corridor will stretch across Eurasia to connect China not only to the Middle East and Europe but also embed it within the region.

One Belt One Road is said to involve Chinese investments of between US$800 billion and US$1 trillion, covering almost 900 projects in more than 60 partner countries – a truly monumental initiative. Several commentators have drawn parallels between the policy and the 1948 US Marshall Plan that helped rebuild postwar Europe.

The US reaction to China’s initiatives has been on two tracks. First, it sought to thwart the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, pressuring other countries not to join. This effort failed spectacularly when the United Kingdom, the most important US ally, became the first to break ranks. The bank now has 50 members, including many US allies from around the world.

US policymakers also promoted the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade agreement linking the United States, Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, Brunei, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Chile and Peru. If ratified by all participating countries’ legislatures, it will be the first real manifestation of President Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia”, which has so far consisted of little more than rhetoric.

China, which is excluded from the TPP, responded by promoting the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which excludes the United States, and which would promote rapprochement between Beijing and Tokyo. The RCEP includes a vast array of rules concerning investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement, and government regulation.

Exceptional allies

This jostling between the US and China for influence in Asia explains why alarm bells started ringing in Washington when the Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte announced a “separation” from the United States. Indeed, quite a lot of Duterte’s rhetoric since his election has brought into question his nations’s decades-long partnership with Washington.

A month later, Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak initiated what seemed like a rapprochement with Beijing when he announced the purchase of coastal patrol ships from China. This is the first substantial defense contract between Kuala Lumpur and Beijing and a significant signal, given the US had also hoped for a deal with Malaysia.

These moves were particularly surprising because both the Philippines and Malaysia are claimants to disputed islands and reefs in the South China Sea. Washington had hoped that the tension there could be used to build an alliance to contain Beijing in the region and put international pressure on China.

The Philippines is the only South China Sea claimant that is also a US treaty ally. The two countries recently concluded the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement, allowing Washington access to five Philippines military sites.

But there are several reasons why the Philippines and Malaysia can be seen as outliers. Their leaders have specific reasons to tilt towards Beijing that don’t apply to other US allies in the region.

Duterte’s controversial “war on drugs”, involving systematic human rights violations, has generated US criticism. And, in Malaysia, Najib has been under pressure after US investigations revealed a giant fraud committed by 1MDB, a state investment fund.

Where to now?

It’s important to also keep in mind that pro-China rhetoric doesn’t always match actions. Malaysia now conducts military exercises with Beijing, but its ties to the US are still stronger. With the exception of North Korea, Laos and Cambodia, China’s neighbours are all still closer to Washington than Beijin.

And the United States remains far more popular than China among Asian people, reflected by the far larger number of Asians who aspire to move to the United States than to the Middle Kingdom.

Nonetheless, the US plan to maintain strong political influence in Asia and build alliances to contain China faces significant obstacles. Many US allies not trust each other (Japan and South Korea, for instance). And this may lead to collective action problems, such as what’s know in international relations theory as “free-riding” – when actors benefit from public goods without making a contribution.

What’s more, many countries in the region are increasingly dependent on China’s economy, reducing their willingness to oppose Beijing. Even though, in principle, they are more likely to oppose China than support it, given its proximity and regional leadership ambitions.

As president-elect Donald Trump’s support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership is very unlikely, and with China’s initiatives entangling the region’s economies with its own, time is clearly on Beijing’s side.

Countries in the region will probably opt for a hedging strategy: maintaining the United States as a security ally, but benefiting from broader economic integration with China.

Some of these, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, could emerge as the greatest beneficiaries of this dynamic, provided they play their cards right. Duterte, for instance, may simply be trying to extract stronger security guarantees from the United States, while obtaining more Chinese aid.

While mounting tensions between the West and Russia and continued instability in the Middle East remain relevant and will require US attention, it’s in China’s neighbourhood where the future of global order will be decided.

Read more:

A Fractured West in a Post-Western World

What a President Trump would mean for Brazil

The Political Economy of China’s New Silk Road

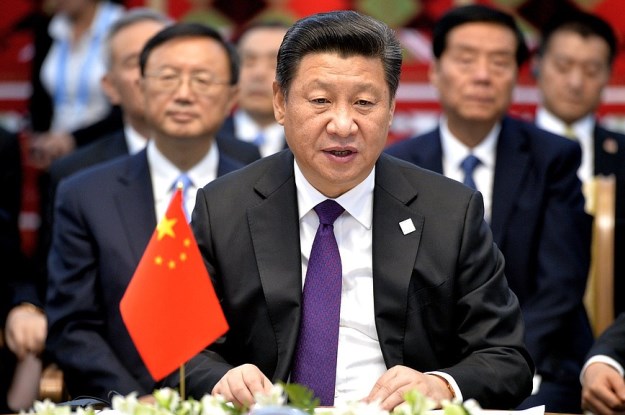

Photo credit : Carlo Allegri/ Reuters